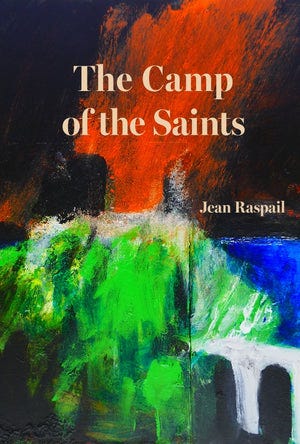

The Camp of the Saints: A New English Edition

A momentous literary event: Jean Raspail's novel is now available

Over the past year, I’ve helped the excellent people at Vauban Books bring out a new English edition of Jean Raspail’s The Camp of the Saints: one of the 20th century’s most haunting, important dystopian novels. It’s ready for you to order.

The Camp of the Saints imagines an armada transporting one million migrants from India to the shores of France. As the migrants draw closer and closer to France, the country, along with the rest of Europe, is thrown into chaos. Paralyzed by self-doubt, loss of principle, and inability to justify the love of one’s own, Europe dies, taking Western civilization down with it.

Published in 1973, the novel was fantasy, written long before mass immigration into the West became a quotidian reality. But it had, to say the least, a certain prophetic character. As the years passed, that made the book more controversial. In the English-speaking world, the novel has been extremely hard to find. Hence the literary event: this is the first time in decades that an authorized English edition has been released.

To guide the next generation of readers, Ethan Rundell has provided a fresh translation of the novel, and I’ve written a new introduction for it. This edition also contains Raspail’s 2011 Preface to the book. Written in the winter of his life, this preface is Raspail’s last testament on The Camp of the Saints. It’s the first time the essay has been translated into English.

The paperback edition is available to pre-order here.

The hardcover edition is available to pre-order here.

Vauban Books specializes in bringing out neglected French thinkers. They’ve published Renaud Camus, whom I’ve written about elsewhere, as well as Jean-Claude Michéa, a left-wing dissident thinker, perhaps even a “conservative communist,” as described in a recent essay for Compact I recommend to you.

Raspail is a great fit for Vauban Books’ growing catalogue.

Now, perhaps you are one of the many intellectually curious people of good will who have some concerns about this novel, given its reception among progressives and racialists alike as a screed promoting white supremacy. I write to reassure you that that conclusion is gravely mistaken, for several reasons.

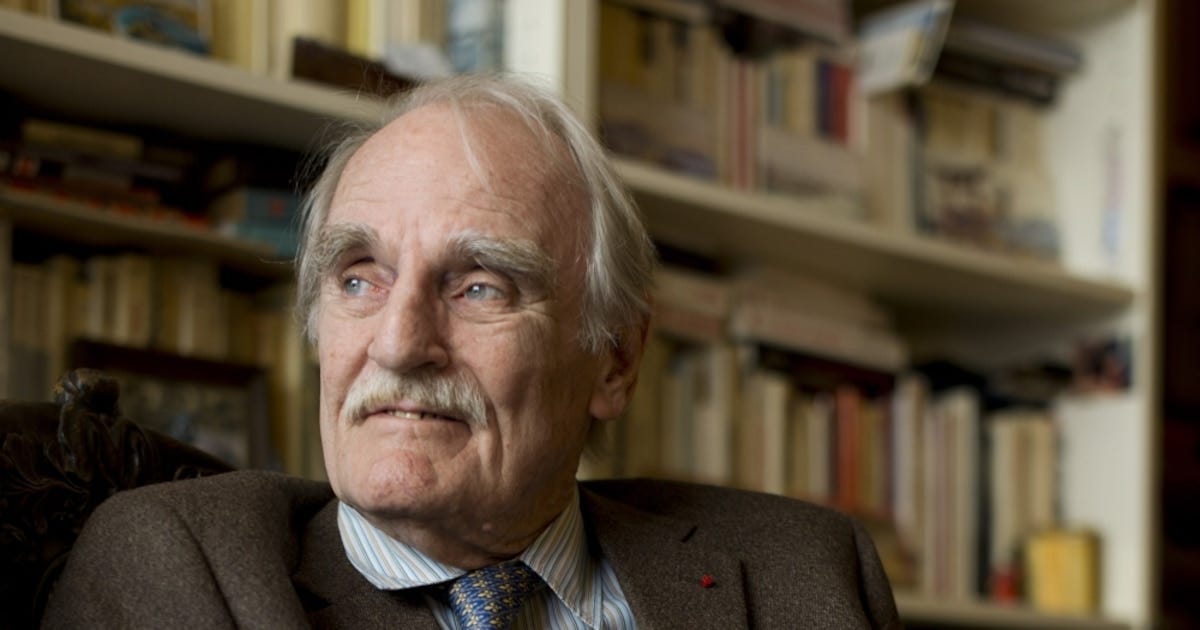

First, Jean Raspail was no vulgar polemicist. The Camp of the Saints was his third novel, and he went on to publish over a dozen novels and around forty books. He received numerous literary prizes during his career, including the Grand Prix de Littérature de l’Académie Française, the same prize for lifetime achievement awarded to Gabriel Marcel, Jacques Maritain, and Marguérite Yourcenar. In 2000, Raspail was nearly inducted into the Académie Française but lost in a close vote. Though Raspail’s faith was Catholic and his politics, to the extent he had any, were royalist, he was on good terms with numerous political and literary figures across the spectrum, including the socialist president François Mitterrand.

When the Prefect of Police of Paris banned a public commemoration of the execution of Louis XVI, Raspail complained on the airwaves. Moved the Raspail’s appeal, Mitterrand intervened. He overrode his Prefect and the commemoration took place.

Second, Raspail made his reputation as a travel writer transmitting the legends and records of many of the world’s disappearing indigenous peoples, from South America to the Far East. His sensibility to the plight of these tribes as they faced potential extinction, as well as his appreciation for their practices, should in itself banish slanders of white supremacy.

Third, close attention to the text of The Camp of the Saints shows that while some passages verge on the sexually explicit or the grotesque (reminiscent of D.H. Lawrence or Michel Houellebecq), interpreting the novel as a racialist screed eviscerates its spiritual core.

The book’s reputation, marred by malicious actors, could have been better served than by Professor Norman Shapiro’s original English translation. Shapiro, a scholar of French poetry, took some creative liberties with the text that rendered it more provocative.

The book has long needed a new translation that stays closer to the text, and Ethan Rundell has provided just that. Read with the help of Rundell’s fresh translation, English readers can ascertain that the critical drama of the novel concerns the West’s spiritual agony.

One incident in the book makes this clear. As the migrant fleet turns toward Egypt, the Muslim captain uses a sensible combination of threat and prayer to prevent the fleet from landing in Egypt. But Westerners cannot do likewise. They belong to a civilization that is in revolt against its own religious genius. This is the key to understanding why, in the novel, Western civilization dies. The divide between “the West and the Rest,” in Raspail’s world, is not a racialist demarcation. The latter has preserved the capacity for spiritual enchantment, but the former has repudiated that:

Two opposing camps. One believes in miracles. The other no longer does. The one that will raise mountains is the one that has kept its faith. It will conquer. Mortal doubt has sapped all energy in the other. It will be conquered.

My new introduction discusses this spiritual loss of confidence and self-hatred at more length. But if you are curious and want to read a shorter primer on the novel first, you can read my essay for First Things, The Spiritual Death of the West.

But never mind what I say about it. You should form your own opinion of the work by reading it yourself. Thanks to Vauban Books, this is now possible. Secure your copy today!