If anything is evidence that we live in Babel, modern parenting discourse has to be it. Had I remained off X/Twitter, I would have remained happily in the dark about the Discourse - whether on sleep training, breastfeeding, daycare - except for my wife’s nightly reports on it. Alas, dear reader, I took the plunge a few weeks ago, downloaded the bird app, and recently saw something that irked me enough to write about it.

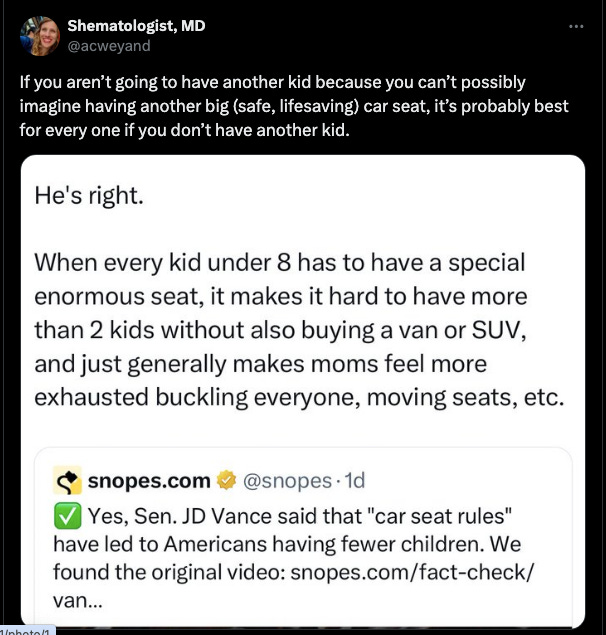

Car seat discourse isn’t new. Four years ago, Catherine Pakaluk observed in First Things that car seat regulations and safety guidelines have evolved to become so stringent that studies are now justifiably blaming them for a decline in the birthrate. According to current norms, most children should be in a rear-facing car seat until age 2 or 3, forward-facing until age 4 or 5, and then in a booster seat for years after - for some children, until age 11 or 12. The car seats themselves are enormous, surely in part because of the size of the older children who are now required to sit in them. Most two-row vehicles — which is to say, anything smaller than a minivan or full-sized SUV - cannot fit three car seats across the second row. The result is that for many families, the decision to have another child is also now a decision to buy a large and expensive new car.

We faced this choice about a year ago. My wife was nearly nine months pregnant with our second child when we finally accepted that there was no way we were going to fit a second rear-facing car seat into our little compact car while leaving enough room for the driver. Because we hope to have more children in the future, we took the plunge and bought a minivan. In poetic timing, we purchased it about nine hours before my wife went into active labor. The van’s maiden voyage was a 5 a.m. rush to the hospital. We were extremely lucky that a bureaucratic error with my wife’s payroll had accidentally fronted us the money to buy the van outright, allowing us to avoid a monthly payment. But most families are not so lucky. It’s not hard to see how the car issue alone could make having another child seem financially prohibitive.

None of this is news to parents of small children. It’s one among the many thousands of things we have to think about that we might never have considered before becoming parents. Nor is it news that a propaganda outlet such as Snopes would attempt a ‘gotcha’ this stupid, as hundreds of people in their replies have pointed out. What’s worth noting, though, is that this is yet another instance of a new kind of political fragmentation that our older political vocabulary doesn’t have the terms to address.

In the 80’s and 90’s, the “culture wars” were battles over a fixed, commonly identifiable set of issues. Abortion is one example; opponents and defenders of abortion see the same issue through completely different moral lenses. If you think of abortion as primarily a question of bodily autonomy and women’s health, you are simply not speaking the same language as someone who thinks that an abortion is the intentional, premeditated murder of a human baby. The two sides approach the problem of abortion from within different moral frameworks. It’s a textbook case of irreconcilable differences; Alasdair MacIntyre discusses it early in After Virtue (1981) as a typical example of why moral dialogue is no longer possible. Whatever political compromises may be available, there’s no solving the debate over abortion at the level of theory. It’s not a debate taking place within a homogenous moral ecosystem; it is, genuinely, a clash between two alien cultures. The polarization that results is bitter, but inevitable.

But in the 21st century, a deeper kind of fragmentation has emerged. There’s no longer a relatively stable set of issues that everyone on the political spectrum can “agree to disagree” about. Rather, what we see is that people on the left and on the right now disagree about what the issues actually are. Partisans in the abortion wars agree, at the very least, that abortion is a real and important political issue. They are typically able to articulate a pidgin version of their opponents’ view. What’s striking about this new fragmentation is that it’s issuing from conflicts over problems that one side is either unwilling or unable even to acknowledge as real.

An obvious example is the question of immigration. Talk to liberals in Vermont or Maine and you might think that mass immigration is a purely theoretical issue. Describe the current conditions in San Antonio, Texas, or Springfield, Ohio, and you might as well be describing conditions on Mars. If your neighborhood or city has not felt the effects of mass immigration, at levels that vastly outstrip the social infrastructure required to support migrants, you might very well conclude that immigration isn’t a real issue. You might then dismiss concerns about immigration as inherently xenophobic, because the practical costs and concrete impact of mass immigration are invisible to you.

It’s this kind of fragmentation that’s on display in the car seat brouhaha. Forty years ago, there would be nothing controversial in suggesting that it is an obvious problem not to be able legally to transport more than two children under the age of 4 in a standard sedan. That’s no longer the case. Fewer and fewer Americans are choosing to marry and have children. Among those who do become parents, most are unlikely to have more than two children. As a result, the prudential concerns that go into having a larger family are becoming increasingly distant to a broad swath of the population. Like Mainers speculating about migrants, many people won’t be able to imagine why or how parents could take issue with car seat regulations. And this invites them to turn up the temperature of political polarization. The unintelligibility of the issue invites a level of moral opprobrium that “agree to disagree” issues didn’t.

This is one of the biggest differences between the culture wars that shaped the boomer generation and the cold civil war that exists today. When boomer Americans “agreed to disagree”, they coalesced around a quaint kind of civic friendship, readily on display in the election jokes of the early 2000s:

It’s easy to be nostalgic for that time, but those who are often assume a “consensus reality” that no longer exists. In the new dynamic, you don’t “agree to disagree:” you accuse the other of disinformation, misinformation, or advancing conspiracy theories. At some level, this reaction makes sense. If you don’t think a problem is real, it gives you all the more license to write off the people who care about it as evil, stupid, or crazy.

Those who advocate for a legal and social infrastructure that is conducive to having larger families are now liable to be written off in the same way. Hence, the rush to condemn Vance’s comments on car seat regulations as a display of callous, cowboy-conservative disregard for health and safety.

For those who are innocent of the intricate Trinitarian mysteries of kids, cars, and car seats, there’s a level at which the reaction makes sense. How, you might think, could a decent parent ever object to something that might make their children safer? It’s a theoretical question asked only by those who have never wrestled with these questions in practice. Never mind the fact that the safety benefits of car seats for older children are disputed. Spend a few weeks researching the prices of gently used Honda Odysseys and you’ll begin to comprehend.

Conservatives have now developed a think-tank apparatus that is becoming more interested in pro-family policies. That’s a good thing, but it’s not going to change the fact that our society is now essentially post-family. Americans, having long ceased to agree on the basic goodness of marriage, no longer agree on the basic goodness of raising children. Fewer still will ever have that experience themselves. As a result, the kinds of policies that actually support marriage and family—financial support for marriage and children, a pro-family public infrastructure, and yes, car seat regulations—are niche interests. The American public at large no longer thinks of these things as general political priorities.

In the post-family politics of the American 21st century, talking about the issues growing families face is a bit like talking about mass immigration in the 1990s. You notice the issue. You may carefully follow policy debates happening in European countries that are grappling with it. You know the classics of the literature. You’re probably a regular reader of the few writers this side of the Atlantic who discuss the problem and propose solutions. But when you speak to a wider audience, you’ll have a hard time. You’ll face a public that finds the specific problems you’re talking about unintelligible. Moreover, you’ll face a powerful and growing constituency that thinks you are evil or stupid for questioning the status quo. And if you’re a national politician in a tight electoral contest, you’ll open yourself to all kinds of attacks.

The tragedy is that we are at the end of a time when the concerns of families with children were decisive to elections. From the 1980s until 2008, the politicians who invoked “family values” had a considerable electoral edge. But these politicians struggled to translate their rhetoric into real policy benefits. Now the inverse is the case. American conservatives are better positioned than ever before to establish genuine pro-family policies. But the electorate has changed. The enemies of the family are stronger and more numerous than they ever were before.

There remain many of us who want to have one more baby (or more). It’s energizing when national figures such as Vance speak to our issues. We notice. But we can’t presume that a majority does too.

Yes, keep the children safe. Like how we were supposed to lock them inside and cover their faces for two years.

Or those live shooter drills for a statistically insignificant phenomenon that scare my kids.

I just hate these people.

If only it were just the car seats.

Here, if you rent (because who can afford to buy a house anymore) you are also subject to fire safety regulations that discriminate against families with more than two children. For "fire safety" reasons that do not take into account the size of the rental unit, or the age of the residents, landlords can cap occupancy at two people per *bedroom*. Which admittedly seems reasonable. Who wants to pack three or more kids into the same room, right? Right up until you realize that landlords hate kids. Kids are destructive. If you have a 4-bedroom house to let, and you could choose between renting it to a family with six young children, or a couple of childless fiftysomethings, you'd pick the fiftysomethings every time. That's not legal, of course. But you know what IS legal? Removing closets.

If you remove two closets from that house, it is no longer a four-bedroom house. It's a two bedroom house with a home office and a craft room, and you can limit occupancy to four. Neat, huh?

So back to the family contemplating a third child: Not only are you going to need a bigger car, if you're a renter, you're also going to have to rent a bigger house. And the jump in rent from a 2br to a 3br in a comparable neighborhood is large *and* it's much harder to find one. This is a much bigger problem than the carseat thing.

Like, of *course* no decent parent is going to make that decision based on the price of a minivan.

But some of them are going to make that decision based on the part where they will have to move all their kids into a much sketchier neighborhood and probably a worse school district, to afford the rent on a three-bedroom house.